“As we construct the past to create a narrative that makes sense to us, we give birth to characters who personify key aspects of the self…..wherein characters “are born” or “come onto the stage.” It is often at a high, low, or turning point that an imago finds a narrative mechanism for coming to be.” (McAdams 128-9)

If Alison Bechdel’s graphic memoir came to be because of a need to shape her story to facilitate the possibilities of multiple truths in her family history, then her reconstruction of her father is therapeutic in the sense that it gave her the compassion to examine her childhood as producing a coherent self in relation to a fragmented family whose members have tragic existences or endings. Instead of Bechdel’s life drawing her, she draws snapshot-like visual-linguistic memories that have contributed to the construction of lives in relation to one another that shaped her identity. Less a child with a history, or a father with a secret, Bechdel draws from the multiplicity of her characters to come to peace with what can not be known: How did her father conceptualize of his own queerness, was his death accidental or suicide, how is she produced by her family and how is she self-made?

Rather than dwell on these questions, she weaves literary myth into personal myth to make meaning and avoid reducing her own sexuality and identity (or her father’s) into existing tropes – while being aware that the concepts of “lesbian” and “father” are societal myths, collectively created imagos – “a standard cast of characters for contemporary identity making.” (McAdams 127). By honoring the non pathologized multiplicities that Carter suggests, Bechdel is able to see her father as intelligent yet destructive, committed and bound but impulsive, yearning to connect but lost in projects, enchanted by the aesthetic and immersed in the literary, urban and rural, bound to the family but at once apart from it even if in desire. It is in this imago construction that she can formulate her relationship to her father and how it has shaped (and not shaped) herself – rather than dwell in the lack of meaning that grows in the unknown. The known seems to be good enough – and sad enough.

If we can’t be what we can’t see (as the concept of imago implies), then Bechdel has also transcended the family as the primary loci for conscious identity formation as an adult: She came to understand her queerness an an identity without conscious awareness of her father’s sexuality. Yet she is shaped by her non-heteronormative parent, queering her kinship structure, whereas the common understanding of “queer family” is usually that of a chosen one. While he uses literature to connect to Alison and she reciprocates the exchange through the creation of Fun Home, further mythologizing the linkages between his desires and hers to find common ground in their differences. She was to identify as queer and transcend the heteronormative restrictions of family that her father was not. Yet she finds connection in the fact that “Not only were we inverts, we were inversions of one another” (Bechdel 98). And even though these fraught connections are “tragicomical,” maybe they’re as close as we get to understanding ourselves and those closest/farthest away from us.

– – –

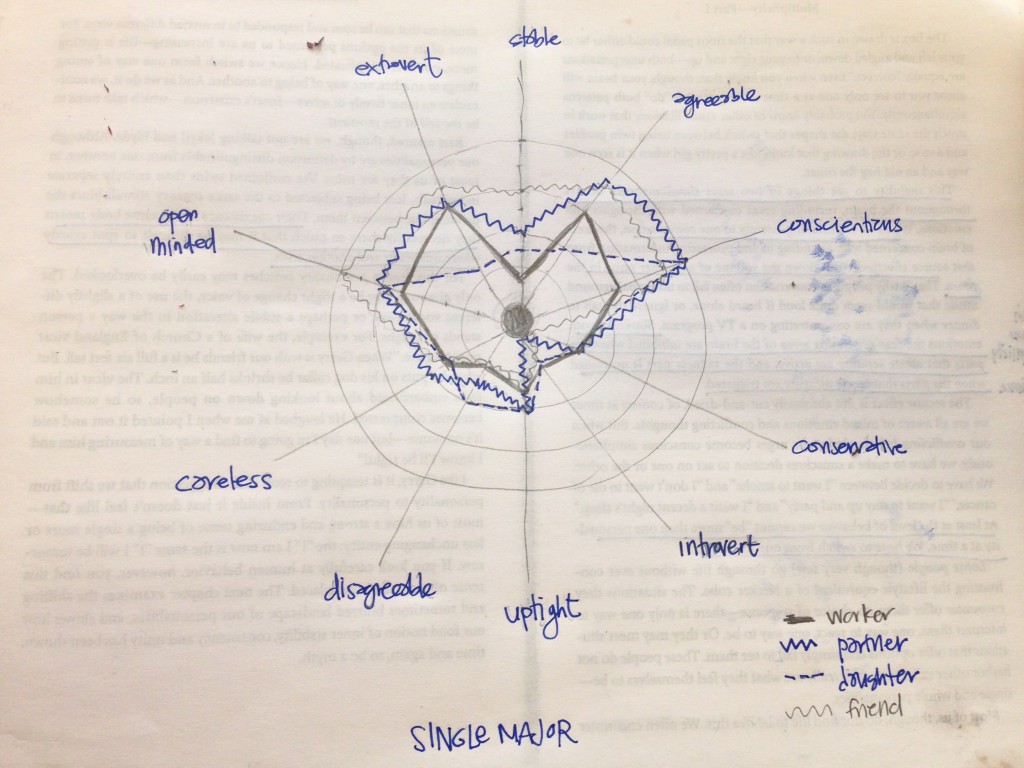

On a complete side note, I did Carter’s Personality Wheel, and was creeped out that I’m an “inflexible and unadaptable” Single Major with a “fairly unchanging life” (Carter 141). Sounds awful. Am I lying to myself? Or am I getting old?

1 response so far ↓

Jason Tougaw (he/him/his) // Oct 8th 2013 at 4:40 pm

Okay, this is pretty funny. I admit I didn’t have the patience to do this myself. Maybe I’ll find the motivation tomorrow. You’d think a “Single Major” would be the American ideal. But maybe that’s what’s creeping you out!