Entries Tagged as 'Uncategorized'

Alison Bechdel’s Fun house brought me back to the conversation we had in class about multiple selves. Not everyone agreed with McAdams’ theory that we have many different imagoes and these imagoes appear at different times in our lives. McAdams also believed that our imagoes “are often embodies in external role models and other significant persons in our adult lives” (123). The character of the father in Bechdel’s autobiographical narrative was representative of McAdam’s theory in that she presented him as having multiple identities. Bechdel question her own identity in connection with her father’s. After his death, she began to feel that she may have taken on her father’s homosexual “imagoe.”

Outside of his home, Bechdel’s father was a teacher, family man who took his wife and children to church, and a funeral director. In his personal life, he was obsessive decorator, a closet homosexual, a dictator, and a pedophile. The father lived his roles so well that Bechdel only learned that he was homosexual after she revealed her homosexuality to her mother.

Once Bechdel became aware of her father’s homosexuality, she then began to examine moments that were missed, like her father’s relationship with the babysitter. She then began to examine how her homosexuality was connected to her father’s homosexuality. She began to see her sexuality as a mirror image of her father’s sexuality; the more feminine her father became, the more masculine she became.

Tags: Uncategorized

October 8th, 2013 · 1 Comment

“As we construct the past to create a narrative that makes sense to us, we give birth to characters who personify key aspects of the self…..wherein characters “are born” or “come onto the stage.” It is often at a high, low, or turning point that an imago finds a narrative mechanism for coming to be.” (McAdams 128-9)

If Alison Bechdel’s graphic memoir came to be because of a need to shape her story to facilitate the possibilities of multiple truths in her family history, then her reconstruction of her father is therapeutic in the sense that it gave her the compassion to examine her childhood as producing a coherent self in relation to a fragmented family whose members have tragic existences or endings. Instead of Bechdel’s life drawing her, she draws snapshot-like visual-linguistic memories that have contributed to the construction of lives in relation to one another that shaped her identity. Less a child with a history, or a father with a secret, Bechdel draws from the multiplicity of her characters to come to peace with what can not be known: How did her father conceptualize of his own queerness, was his death accidental or suicide, how is she produced by her family and how is she self-made?

Rather than dwell on these questions, she weaves literary myth into personal myth to make meaning and avoid reducing her own sexuality and identity (or her father’s) into existing tropes – while being aware that the concepts of “lesbian” and “father” are societal myths, collectively created imagos – “a standard cast of characters for contemporary identity making.” (McAdams 127). By honoring the non pathologized multiplicities that Carter suggests, Bechdel is able to see her father as intelligent yet destructive, committed and bound but impulsive, yearning to connect but lost in projects, enchanted by the aesthetic and immersed in the literary, urban and rural, bound to the family but at once apart from it even if in desire. It is in this imago construction that she can formulate her relationship to her father and how it has shaped (and not shaped) herself – rather than dwell in the lack of meaning that grows in the unknown. The known seems to be good enough – and sad enough.

If we can’t be what we can’t see (as the concept of imago implies), then Bechdel has also transcended the family as the primary loci for conscious identity formation as an adult: She came to understand her queerness an an identity without conscious awareness of her father’s sexuality. Yet she is shaped by her non-heteronormative parent, queering her kinship structure, whereas the common understanding of “queer family” is usually that of a chosen one. While he uses literature to connect to Alison and she reciprocates the exchange through the creation of Fun Home, further mythologizing the linkages between his desires and hers to find common ground in their differences. She was to identify as queer and transcend the heteronormative restrictions of family that her father was not. Yet she finds connection in the fact that “Not only were we inverts, we were inversions of one another” (Bechdel 98). And even though these fraught connections are “tragicomical,” maybe they’re as close as we get to understanding ourselves and those closest/farthest away from us.

– – –

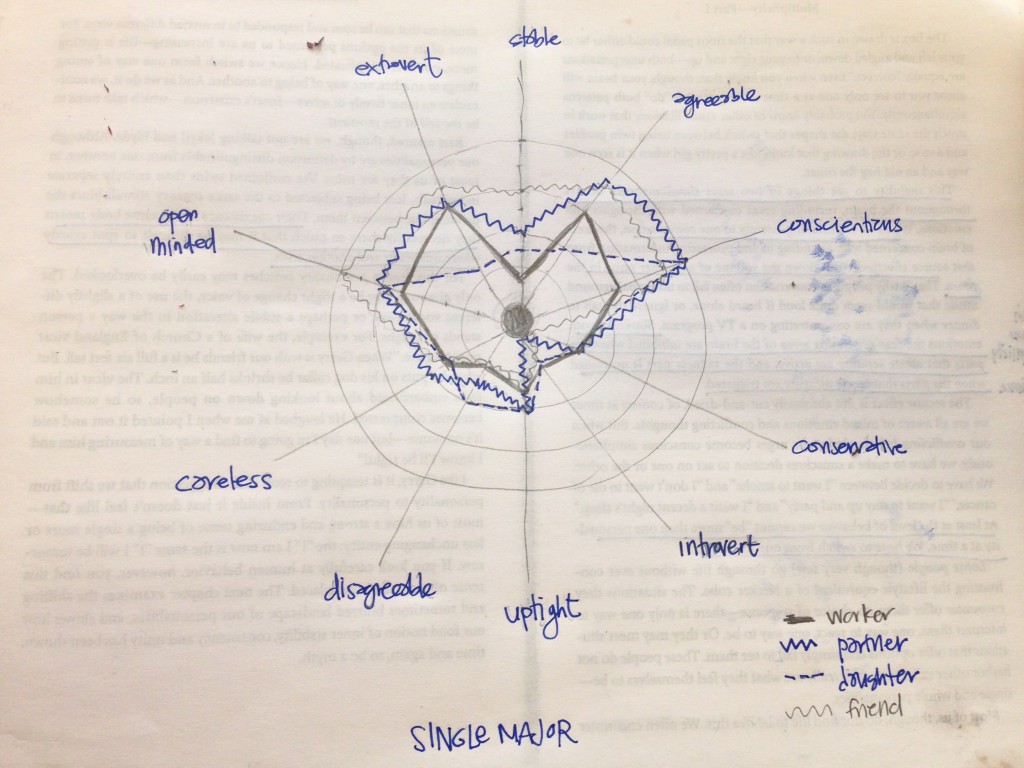

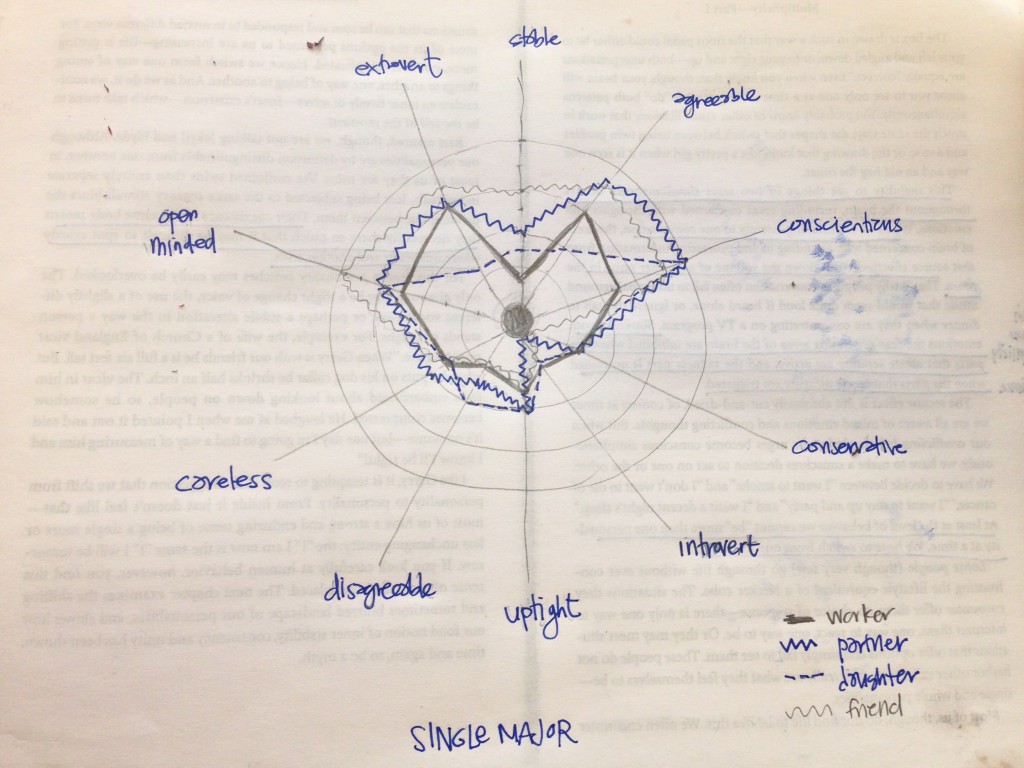

On a complete side note, I did Carter’s Personality Wheel, and was creeped out that I’m an “inflexible and unadaptable” Single Major with a “fairly unchanging life” (Carter 141). Sounds awful. Am I lying to myself? Or am I getting old?

Tags: Uncategorized

I really enjoyed “Fun Home” and the way Bechdel uses references from literary sources to fuel the development of the “characters.” As I read Rita Carter’s chapters, I couldn’t help but mentally put Alison’s father through the Personality Wheel exercise. The way he is described throughout “Fun Home” seemed to closely match the multiples Carter was describing. In no way did I think of Mr. Bechdel as having MPD, however, he clearly displayed the ego-states of multiplicity of personality. He seemed to move seamlessly between different personality types throughout the book, and that quality was apparent specifically in his character description. The opening pages seem to set this up even from the title of the first chapter, “Old Father, Old Artificer.” We can see the different disjunctive selves he had to maintain and understand the character through each: The English professor, the mortician, the father, the husband, the closet homosexual. He seemed to display what would be classified as the Major-Minors multiple, however, although Major-Minors are often stable when each personality compliments each other, his closet homosexuality was in discordance with the rest. This caused unrest in his personal life and might have ultimately, as Alison Bechdel suggests, caused his demise.

Tags: Uncategorized

I think Bechdel really illustrates (puns) Macadams’ idea of the personal myth in Fun Home, establishing the literal Greek myth of Daedalus and Icarus as a recurring theme throughout both Alison’s life and as an inherent framework for this autobiographical “tragicomic”. What struck me was how, and at such a basic level, other well-known texts infiltrate and contaminate this story, particularly Gatsby and Ulysses, and even these correspond with the Icarus myth (“Stephen Dedalus”, the idea of ‘flying too close to the sun’). I completely buy the idea behind personal mythmaking, and how this process becomes blurred between fact and fiction and fiction again. The first fiction is the subjective personal history constructed retroactively by the self, and while this is crucial to setting up a personal continuity that allows for decision making and future growth, the second fiction – actual, creative, fictional stories that exist outside of the personal experience (like Gatsby or Icarus) – can hold just as much sway over a personal mythology.

McCloud’s Understanding Comics is amazingly insightful as a piece of philosophy, looking at the interaction between storytelling and media and audiences even outside of the comic genre. While I hadn’t originally thought of using the McCloud as a lens, it’s obviously very helpful in any graphic analysis. His concept of “closure” is one that is particularly demonstrated in Bechdel, on multiple levels. The reader is forced to perform closure throughout the graphic novel, mediating the text and images and the action Bechdel is framing, making logical jumps during the gutter inbetween panels. “Closure”, as related to reader identification, also takes place, as the simpler, cartoon style allows a relationship between Alison’s characters and the reader to develop quicker and easier than it would if the drawing style took on a more realistic or nuanced approach. A kind of “meta-closure” also exists within the world of the story, as the characters identify with other historical figures, fictional characters, or periods/groups/movements (Ex: Mr. Bechdel and Fitzgerald/Gatsby, Alison and Woolf/Orlando/The Gay Community at college).

McCloud builds a mythos around comic books (and indeed, there is the notion of the superhero mythos) related to identification and closure and built upon this approachability combined with iconography. Alison’s illustrated characters win our sympathy through our process of closure; we fill these simple drawings with our own voices and ideas and experiences. Fun Home capitalizes on the preconceived set of comic book iconography, purposely eschewing the more traditional genre pieces of superheroes, action and adventure, or sci fi by utilizing the genre to instead tell an auto-biographical story definitely grounded in reality. Once again, there is something meta happening in Bechdel, as her characters form strong opinions and impressions and, what I’d argue are components of personal myths, around real-world icons of movies, novels, and writers, within the story. (Interestingly, Gatsby and Stephen Dedalus and Orlando and other popular novelistic characters are often described as “iconic” – even though I believe McCloud is specifically referring to images as icons, texts can become icons just as easily, and serve the same roles of touch-stones for identity)

This got kind of rambly – as these informal blog posts inevitably do – but I wanna slip into my Disability Lens (as I inevitably will) before I sign off. I thought it was interesting, and certainly relevant to the idea of the self as being governed by the environment, interaction with objects, and other selves, in the way Bechdel frames her childhood Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (as well as her attitude towards family, and, to some extent, her homosexuality) in relation to her father. The family can be conceived of as both an external and an internal force working on Alison’s sense of self; she is a separate individual and yet her experience, her existence, is completely modulated through the family she grows to adulthood in. Alison’s girlhood obsession with ritual and numbers can be seen as an attempt to enact control, due to or in spite of her distant yet controlling father – we can see an argument form for the inception of mental compulsion by outside forces. Similarly, her relationship with her father is again implicated (although I’d argue this is meant to be complicated and critical) when Alison comes out to her parents. The visible portions of the letter her mother writes stigmatize her homosexuality and quantify it as being caused by Mr. Bechdel; taking into account the history of social perception of homosexuality, Mrs. Bechdel equates Alison’s lesbian-ness with her earlier OCD, and ascribes them both to the father. The figure of the abused daughter as stigmatized/disabled victim and the stereotypical butch image are both powerful archetypes and both seem to be at play in Fun Home, and now that I’ve come full-circle to image and icon and their role in personal myths, I’m wondering what everyone else thinks?

Tags: Uncategorized

October 6th, 2013 · Comments Off on Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics

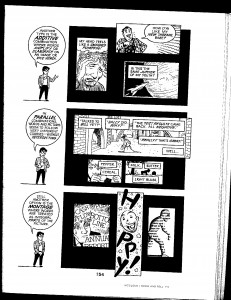

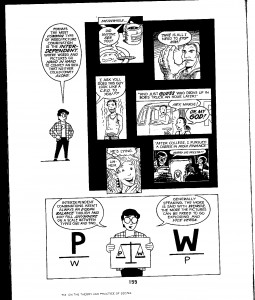

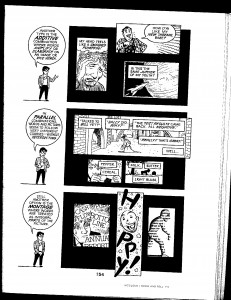

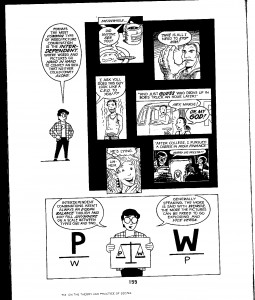

Hi everybody. In class, somebody proposed the idea of creating a graphic novel as a research project. (I think it was Sabrina.) It doesn’t sound like anybody feels qualified to do that, but Scott McCloud did. He wrote a book of literary criticism about comics, entitled Understanding Comics–and he did it using the comics form. I’ve put two chapters of the book on our readings page, and I’m including a few pages on this post.

I’d like you to take a look at McCloud’s explanations of the variety of ways that words and image can work together to produce meaning. Then, choose a panel or page from Fun Home that uses some of these techniques to represent selfhood. Be prepared to talk about your chosen panel or page–and the ways it might show us what’s unique about Bechdel’s chosen genre. What can a graphic narrative do that other forms or representation or inquiry cannot? Those of you posting this week might also want to consider using McCloud as a lens to discuss Bechdel for your reading responses.

Tags: Uncategorized

October 3rd, 2013 · 1 Comment

Hi everybody. I’m posting a fairly typical call for papers for an anthology like the one we’re talking about putting together for this course. This call is for a special issue of a journal, but it’s pretty similar to CFPs for book anthologies.

I’m thinking about creating the assignment by putting together a call like this, where I’d be the editor and you’d be the contributors. I thought it would be helpful for you to see this one. If anybody comes across other CFPs, I encourage you to post them.

Modern Fiction Studies

Call for Papers: Upcoming Special Issue

Neuroscience and Modern Fiction

Guest Editor: Stephen J. Burn

Deadline for Submissions: 1 February 2014

The Editors of MFS seek essays that consider how modern fiction has evolved in dialogue with the neuroscientific revolution. In the aftermath of the so-called “Decade of the Brain” (the 1990s), a new wave of accessible surveys of brain research propounded a neuro-rhetoric that increasingly presents itself as the authoritative mode for addressing the total constellation of experience that once constituted the novel’s natural territory. But while scholars have drawn on the new sciences of mind to retool narratological studies and to facilitate Cognitive Historicist readings of classic literary texts, literary critics have rarely explored the ways that modern fiction has absorbed or contested the influence of neuroscience thought. What implications does the fertile intersection of neuroscience and narrative carry for fiction’s traditional building blocks (character motivation, plot structures, narrative architecture)? How does the novel’s language evolve in response to neuro-rhetoric? In terms of the broader conceptual issues, how is the neuroscientific conception of the self challenged or explored in fiction? What are the epistemological consequences of neural determinism for the novel’s fascination with contingency? How do our notions of genre evolve in a neurocentric age?

Such examples are indicative not exhaustive, and we invite essays that explore how modern fiction has engaged with the new sciences of mind. Essays on individual writers and works are welcome, as well as essays on broader trends and issues raised by literature’s cross-fertilization with neuroscience.

Essays should be 7,000 – 8,500 words, including all quotations and bibliographic references, and should follow the MLA Style Manual (7th edition) for internal citation and Works Cited. Please submit your essay via the online submission form at the following web address: https://www.cla.purdue.edu/english/mfs/special_issues/

Queries should be directed to Stephen J. Burn (Stephen.burn@glasgow.ac.uk).

Tags: Uncategorized

October 2nd, 2013 · Comments Off on

Tags: Uncategorized

This week’s readings brought to my mind the eternal philosophical question of which came first, the chicken or the hen? Narrative Theory and the perspectives of identity seem to be putting forward Noe’s insistence of the relation between self and society, and in this sense bringing up the inquiry of the relation between the development of society and the development of self. The descriptive use of phases through which the self evolves, with a time wise orientation, can be very much compared to the phases through which the progress of social and material development are understood chronologically through history.

The eternal loop that this duality generates is sensed in McAdams internal debate as to how individual myths can influence social ones, and vice versa. Where: “Some stories gain wide acceptance for their ability to communicate a fundamental truth about life.” (p. 33); or, “A society’s myths reflect the most important concerns of a people” (p.34). The meshing between social and individual myths can create a questioning as to where the self becomes realized, as to what part of life caries more weight in the invention of the self; either in personal conceptions of society or the general social conceptions that affect our personality. Narrative Theory in a way makes behavior seem like the place where to search for the self; are we polite because we internalized that being so is a good quality, or a we so because society will deem it worthy?

Still with this said, the search for the self through the narrative capacity of individuals gives much opportunity to the possibility of agency that maybe a biological notion of the self doesn’t find a place in which to consider. The capacity of evaluating the narrated past, and the constantly mentioned foundation, gives individuals the tool of continuously editing their stories. Something that possibly the biological description of brain mapping and memory with mechanisms that reduce the brains efforts may not be able to grasp. This new shift in the standpoint of inquiry, as did the others, creates further questions, something that personally transforms into the question of where does unconsciousness lie within Narrative Theory? How can the mind’s unconscious activity be captivated by narrative action? Questions that Damasio’s and Hustvedt’s accounts seem better prepared to answer.

Tags: Uncategorized

The conversation of narration and the self in the reading for this week were, to me, very insightful. Lazlo’s piece focused on the psychological (and rather technical) argument of the ‘root’ of knowledge regarding the self and the symptomatic value of this understanding through . This took me back to the course that I took in my undergraduate class where we studied the personality with diagrams and theories, which is a similar approach that Lazlo uses. What were really compelling were the two short reads from Dan McAdams as he explored the idea of storytelling, narration and the self.

Before I venture off into the positive components of his pieces, I wanted to address an issue that I had with his use of the word “myth.” The word here is used to describe the personal encounters that individuals face that assists in establishing the idea of self, however, I was initially turned off by his word choice. Myth refers to a fictitious events that are generated by the senses but in the story of Margaret Sands, this was a tangible narration of her life story, one that was real even if she herself didn’t want it to be. I puzzled at this point throughout the reading of Personal Myths and the Making of the Self because he makes it a point to repeat this notion, especially when he describes verbal accounts as “internalized personal myths” and the reference to imagoes. Despite the fact that I appreciated the inclusion of Margaret’s story and the segment on the narrating mind, I couldn’t get past the association of myth and personal encounters. It just didn’t seem logical and a part of me was disturbed by the possibility that the my life its experiences are merely mythological.

At that point I had to take a step back, order a coffee and make an attempt to figure out a method of reasoning as to why he would make such a comparison.

After another run through of this and Story Characters, I came to realize that I was over thinking the logic and possibly taking it too literal. McAdams makes a useful point that each of us has a narrative mind and that mind produces stories involving characters and plot based emotional and environmental exposures. In a way our lives are the stories that the self elaborates. Our psychological thought processes make us aware that these experiences are real but they can still be considered the fabrication of our mind’s conceptualizations.

This was a creative revelation for me and I was happy to have that sort of experience with his writing because that’s what makes good writing.

Just to touch on a few other things that I found interesting, I sensed a bit of Damasio in the idea that McAdams agree that the identification of self through personality is fostered on the environment. Also his pieces also focused on the discussion of illustration, imagery and tale-telling which is a perspective that we don’t always here about in the discussion of mind and self.

More importantly, I now understand the myth.

Tags: Uncategorized

As I mentioned in class, I entitled my concentration at Gallatin while at NYU “Narrative Theory.” I thought this was an apt title for numerous reasons. It sounded exotic enough. And it suggested the study of many things I was interested in. In retrospect, I cannot say that I really did “narrative theory” as it has evolved in the academic world nor can I say that I actually fully understand it. There was an idea, a type of study that I was interested in doing, but I don’t know if I ever did it, or whether it actually has to do with “narratives.”

This class is kind of exciting because it is the first time that I have taken a class that directly deals with “narrative theory.” And I have to admit, I don’t know if I like it. Not that I don’t enjoy the class. I do. But I am not sure whether thinking in terms of “narrative” actually adds anything to an object of study or further obscures it. It definitely reorganizes our conception about the object of this course’s study. This week, psychologists affirm the value of using narratives for psychological analyses of identity. While at first, there may be an “aha” moment when we read McAdams and Laszlo, since their approach makes sense, especially after reading Damasio. Well, really, all the readings support this method. But Damasio is the “real” scholarly support because his work presupposes the cultural currency of “scientific” authority. “Storytelling is something brains do, naturally and implicitly” (Self Comes to Mind 311). But how? And why?

On the other hand, there is also a type of reductionism that occurs in recapitulating identity analysis through story grammar. By invoking narrative, the object of study (consciousness, identity, self) becomes imaginitive. Its existence has only a sociolinguistic reality. At the same time, now we have to figure out what the hell a narrative is and why brains do it “naturally and implicitly.” McAdams makes the same claim without substantiating it, “Human beings are storytellers by nature . . . many scholars have suggested that the human mind is first and foremost a vehicle for storytelling. We are born with a narrating mind, they argue ” (27-28 my emphasis). Who exactly says this? Well, Damasio claims that evolution selected the storytelling gene, teleologically presuming that individuals and cultures had a better chance of survival if they could tell stories. Maybe.

I still see narrative analysis useful. I decided to read the UN’s HDI report today, “The Rise of the South: Human Progress in a Diverse World,” and I thought I should share it. Reading this study after reading McAdams and Lazslo article, there was a second “aha” moment for me. If you apply story grammar to the study you can see that a moral narrative is at play. Particularly how nation-states are conceived as individualized characters and how this type of configuration erases and homogenizes their populations. Even embedded in the title one can here an echo of Christopher Nolan’s the Dark Knight Rises. There is a lot more, but I don’t want to spoil the fun. Also, check out page 4 where Amatrya Sen discusses Thomas Nagel’s paper “What is it Like to be a Bat.”

I suppose I can find narrative analysis is useful as long as so called “truth” isn’t presupposed from it. What was interesting to me about the idea of “narrative theory” was using story grammar to analyze society and history. That you could see in studies like the UN’s HDI report that objects, social groups, and/or individuals were being privileged through the mechanisms of storytelling. And, by recognizing the narrative grammar embedded in this study we can subsequently deconstruct the rhetorical hegemony being produced.

If I have to sum up my “irked” feeling, I would say that by applying narrative analysis to the study of the “self” we can understand how this self comes into existence. This week’s reading we are reverting back to the study of identity through a cartesian lens. I think Alva Noe is right to say that the science of self privileges the mind without acknowledging how the world and body are fundamentally integral to its existence. “Narrative identity” produces the same barriers by isolating the subject. The closest we come to moving beyond this is when Lazslo discusses “life story as a social construct” (126). But the analysis is limited.

http://hdr.undp.org/en/media/HDR2013_EN_Summary.pdf

Tags: Uncategorized